Early Friday morning, my dad died. Twelve hours later, I was on a plane to Disney World.

My dad, or Duke or Dukie as my kids knew him, was diagnosed with tongue cancer on April 21, 2017. For at least two years prior, he had a tumor the size of a tennis ball growing on the side of his neck but refused to see anyone about it. After seeing his own father struggle with cancer treatment nearly 40 years earlier, he always told us if he got cancer he’d treat it himself in the backyard with a shotgun (he didn’t even own a gun).

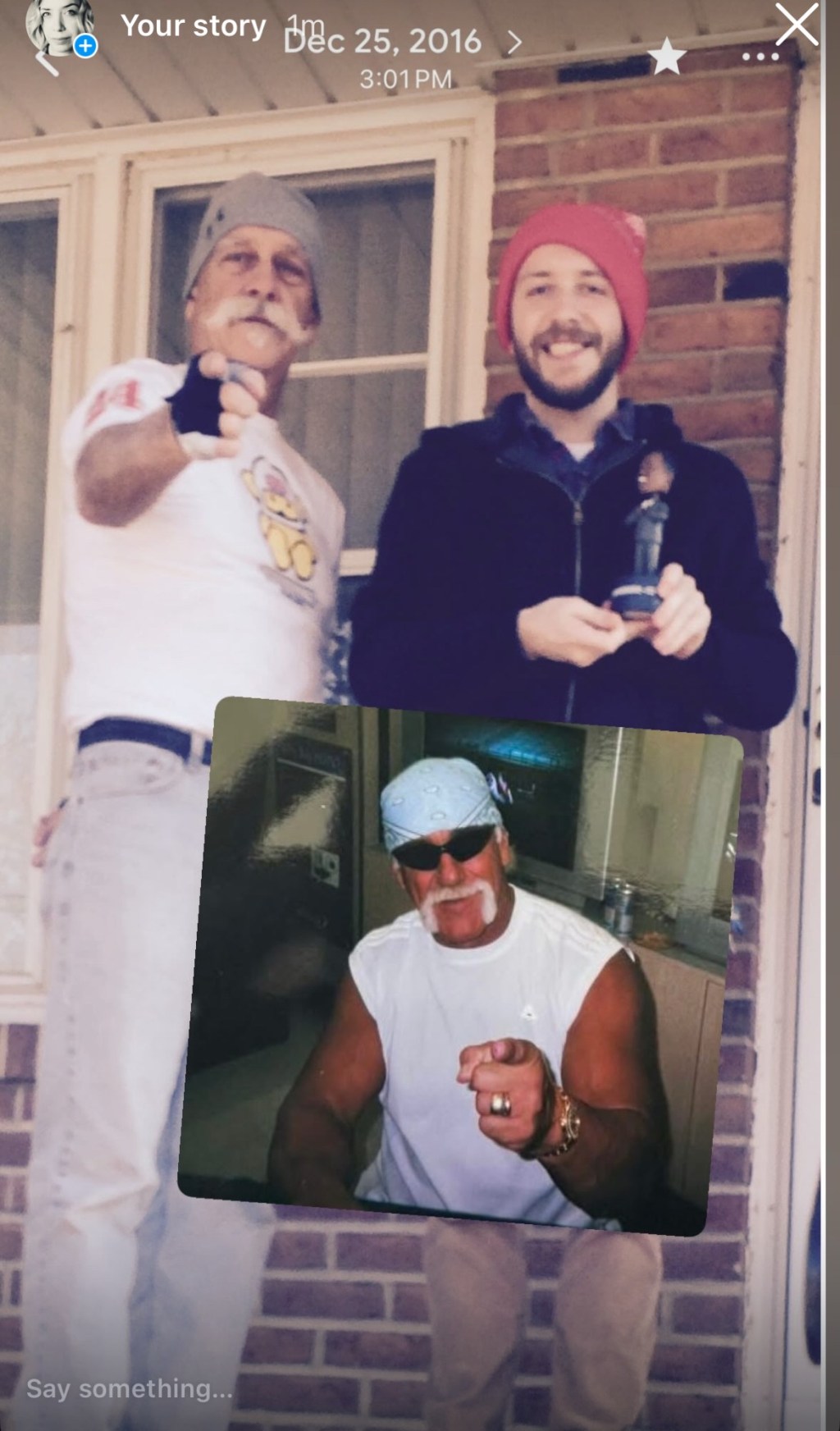

He ultimately relented to our pleas and sought medical help. Three months, 35 radiation treatments, four rounds of chemo and five hospital stays stole my dad’s signature facial hair, about 40 pounds (then 60, then 70), and his ability to ever eat solid foods again.

In healthier times, Dad spent much of his life behind the bar of the bar he owned. Despite the smoky setting, it was HPV, not secondhand smoke, that caused his cancer. By the time of his diagnosis, he had been retired for 10 years and was relishing his roles as babysitter of my kids, amateur furniture maker, avid cyclist and runner, and guerilla landscape artist. Some of his more “well-known” pieces included a ghost bike on our local Rail Trail to commemorate the death of a cyclist, literal tombstones on his front lawn to signify the “death of democracy” (2016), and a larger-than-life 2020 Trump Baby balloon. Many people were gifted a Mark Hess-made garden stone or decorative lawn bicycle, whether they requested one or not.

Dad was what I like to call a tropical traveler. On his last day of lucidity, he bragged that he had visited every location name-dropped in the Beach Boys’ song, “Kokomo,” and then some. My dad loved to travel to the beach and warmer climates, rousing us at four in the morning to get on the road while singing Harry Nilsson’s “Gotta Get Up,” much to my teenage dismay.

He had a year-round tan, his bronze skin crinkling around his grey eyes when he smiled. Until the birth of my children, I had never seen him smile so wide as when we were in Walt Disney World. We had been members of the Disney Vacation Club since 2002. Working in the service industry his whole life, my dad delighted in the hospitality at the resort. He loved hearing, “welcome home,” the DVC catch phrase. And when we were in Disney, this sometimes stoic, quiet man wouldn’t be able to contain his childlike enthusiasm, even after dozens of visits.

The last time we visited Disney as a family was in 2019. Dad was significantly weaker by then and had to take frequent breaks and beg out of some of the parks. One of the standout memories of that trip was the care that was taken of my dad and his liquid diet by the Disney cast. Chefs would come out of the kitchen to personally serve him their puréed concoctions. It was a level of attention that I know Dad found embarrassing, but perfectly encapsulated everything he had loved about Disney in the first place.

By Thanksgiving 2020, Dad had entered hospice care at home. He was surviving on Ensure, hot tea, and CNN. His goal went from seeing his grandchildren grow up to “living to see 70 (on March 30); after that maybe sit in the sunshine for a while.” So confident was I in his ability to reach that goal — and so in need of respite after a year of pandemic living and remote learning — that in March, I put my recently vaccinated husband and myself on a waitlist to go to Walt Disney World the weekend of his birthday, 13 days before my dad’s.

On the morning of Saturday, March 13, 2021, we got the good news that the waitlist had come through. Later that day I got the call from my mom that dad was “ready” and he wanted to “start the morphine.”

There’s this perception that morphine means the end: that morphine actually speeds up death. There is no evidence that morphine hastens the dying process when a person receives the right dose to control their symptoms. In fact, research suggests that using opioids to treat pain or shortness of breath near the end of life may help a person live a bit longer. The result of starting the morphine, for us, was a happier and more relaxed Dad.

On Sunday, we experienced what’s known as the “golden hour,” though we didn’t realize it at the time. He was alert, happy, joking. He saw my kids. He saw my husband. We gave him a gift I had made at my mom’s request: a subway-style sign representing all of the places they’ve ever visited on vacation, prompting that aforementioned Kokomo shout-out.

Monday around 12:15am, I received the call that would really signify the beginning of the end: Dad had slid out of his chair and Mom couldn’t get him back up by herself. I headed to my parents’ house and wouldn’t really leave again until Friday morning.

On Monday afternoon, Dad was asking for my brother, who lived about 30 minutes away. When we told him that Max was on his way and currently on the bridge, Dad replied, “so am I.”

We surrounded him in his chair, held his hands, and held each other. At one point he asked us, “How did I do?” He took a deep breath and closed his eyes as we assured him he did real good.

I believe my dad thought that once he had decided to die, he could simply will his body to stop working. After a few beats, he peeked out through one eye, seemingly disappointed to still be “here.” Unfortunately, as anyone who has supported a loved one through the end of life knows, it doesn’t work that way.

Much to his chagrin, we transported him to a hospital bed in the dining room. He couldn’t get comfortable and was consistently agitated. Consciousness aggravated him. Living aggravated him. At one point he put a pillow over his face and begged me to smother him.

He went to sleep around lunchtime on Tuesday and didn’t really rouse again, except to cartoonishly raise his bushy eyebrows at me on Wednesday morning when I asked if he wanted the “good stuff.”

I smudged the room with sage. I decorated the space to look like a tiki bar for reasons I can’t articulate. I crawled into bed with him and played Bob Marley, Steppenwolf and Paul Simon’s “Graceland” album. I watched as his breaths got shallower and further apart, but refused to stop altogether. They don’t tell you this but by the end, you’re praying for them to stop (regardless of your religious affiliation).

On Thursday afternoon, my mom and brother sat me down and told me I still had to take my trip to Disney World the next day. It was what Dad would have wanted, they said. Dad didn’t want a funeral. I had already written his obituary and handled the funeral home and cremation plans. There would be nothing for me to “do” at home. But I couldn’t fathom going anywhere while Dad was still on the brink.

That night, we decided that none of us would sleep in the room with him. Peter, his amazing hospice nurse, had told us that sometimes the patient is waiting to be alone. By that point, we were willing to try anything.

Around 10:30pm, I sat next to Dad on his bed to wish him goodnight. I leaned down and whispered in his ear, “Dad, I’m supposed to be getting on a plane to go to Disney tomorrow, but I’m not going anywhere until I know you’re where you need to be.”

An hour later, Mom was waking me up to tell me he was gone.

*****

In 2018, Nicole Chung published a beautiful piece, “Mourning at the Magic Kingdom,” in Slate. I bookmarked it at the time, without realizing it would become a blueprint for me to begin to deal with my grief.

We didn’t tell many people that we were taking this trip to Disney. I felt ashamed, I suppose, to be hopping on a plane 12 hours after my dad had died… and still in the midst of an unending pandemic. The three hour flight delay seemed like punishment for me to even consider visiting the most magical place on earth that day. But as my husband and I sat in silence waiting to finally board, “Kokomo” began to play over BWI’s speakers and I felt like maybe, just maybe, Dad was telling me it was going to be okay.

That wasn’t the only time my dad sent me messages with music during that trip. Throughout our weekend, my heart would stop as I heard “Magic Carpet Ride” (grabbing coffee), “Lime in the Coconut” (in the hotel gift shop), and “Is This Love?” (at a poolside bar).

As Nicole had shared, Disney World was surprisingly not a difficult place to be while in mourning, precisely because of that hospitality my dad had always enjoyed. When we visited guest services for an “I’m celebrating my birthday” button for my husband, I asked the cast member to write one for me: “I’m celebrating my dad’s life.”

The first time we watched a cast member’s face switch from joy to confusion and discomfort as they wished my husband a happy birthday and then read my button, we laughed so hard I peed a little. It was the first time I’d truly laughed in weeks. It was the start of so much laughter that weekend: at inside jokes, at memories, at each other. Here, in this magical place, I was able to not just be a mom, a wife, a caretaker, a grieving daughter: I was able to be me.

And there were tears, too. That first night, I experienced a cathartic peace as I sat in a hot tub overlooking the Seven Seas Lagoon and the Electric Water Pageant, letting my silent tears mix with the chlorine and steam.

We were taking a break on a bench in the World Showcase when I saw that my dad’s obituary had been published online. We held each other and cried as we read my words aloud and then laughed again when concerned cast members approached us to make sure we were okay.

I’d love to tell you that this trip healed me and that I returned home healthily in my bereavement process. The truth is that I just found more ways to delay that process: by focusing on work, by clearing out the house, by helping my mom retire and move to the Florida Keys, by focusing on my kids’ grief. It wasn’t really until August, five months later, that I started to really experience my own mourning process. That catalyzed a several-month depression that I’m still not really out of as we come upon the one year anniversary.

We’re now heading into the firsts of the lasts. The last time my kids saw him. The last time he laughed. The last time he was awake. The last time he took a breath.

We have booked a trip to Disney for the whole family the week after the anniversary of Dad’s death. We’ll remember him there, in one of his favorite places, and celebrate his life together as he’s welcomed home for the last time.

I know this trip won’t make me whole, won’t heal me. But I do know that, at least a few times while we’re there, I’ll feel happy. And after this past year (two years? five years?), we’ll take what we can get.